Authors: Álvaro Rodríguez, Santiago Sainz.

Executive Summary

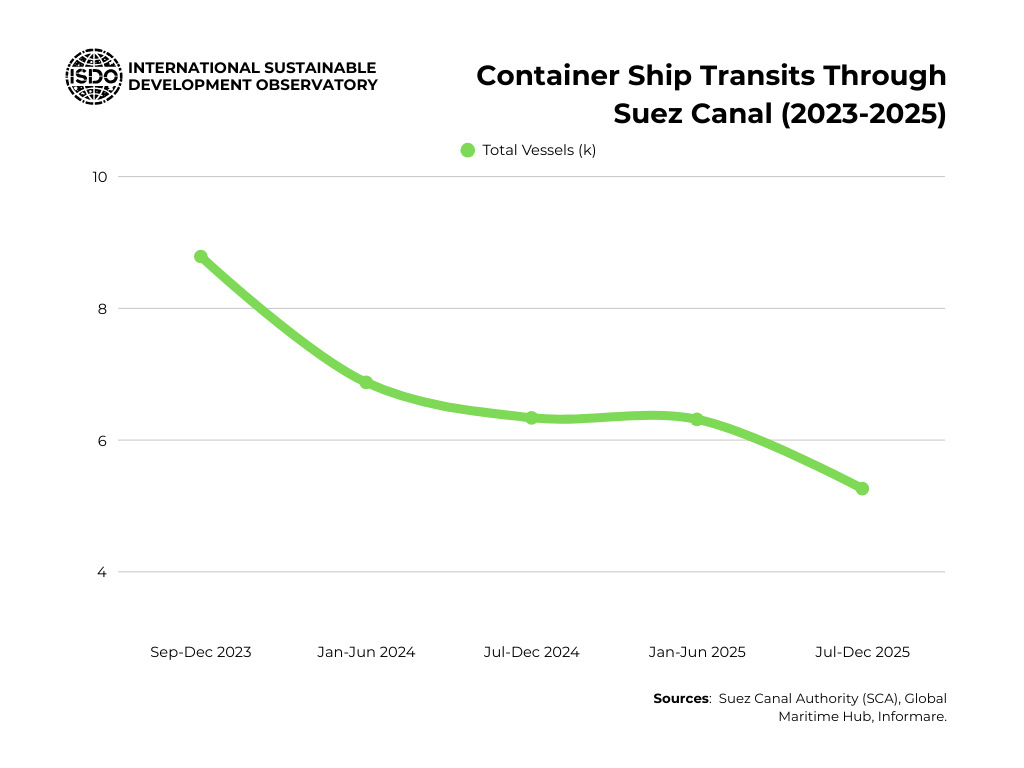

The Red Sea crisis, triggered by Houthi attacks on commercial vessels since late 2023, has transformed one of the world’s most critical maritime corridors into a persistent geopolitical flashpoint. Despite a sharp reduction in attacks following ceasefire arrangements in 2025, traffic through the Red Sea and Suez Canal remains structurally below pre-crisis levels—Red Sea and Bab el‑Mandeb transits in 2025 fell to around 35–40% of 2023 volumes, and Suez Canal traffic in early 2026 remains roughly 60% lower than before the diversions began. This indicates not a temporary disruption, but a durable reconfiguration of global route choices driven by risk perception, insurance markets, and contract structures, rather than by formal cessation of hostilities alone.

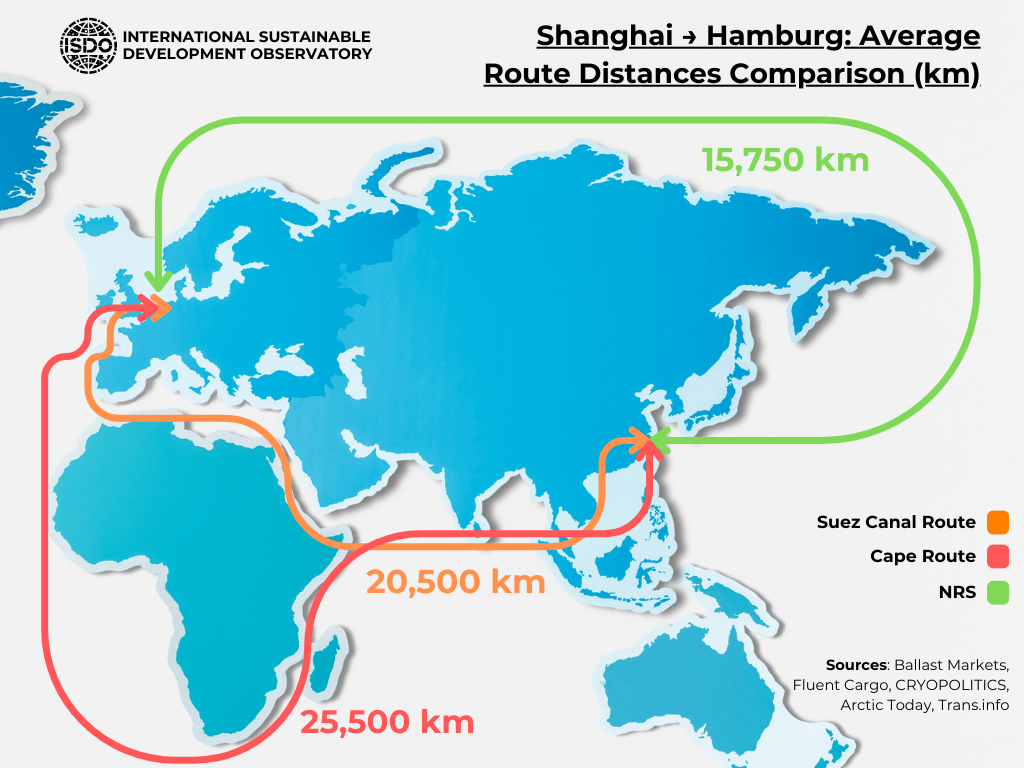

The diversion of traffic around the Cape of Good Hope has added 6,000–11,000 nautical miles and 10–14 days to many Asia–Europe voyages, raising operating costs by up to around US$1 million per trip in fuel alone and contributing to elevated freight rates. While some container and tanker operators have cautiously resumed Suez transits following tentative de‑escalation, a significant share of global traffic continues to avoid the Red Sea, suggesting the emergence of a “dual‑route equilibrium” in which resilience is prioritised over efficiency.

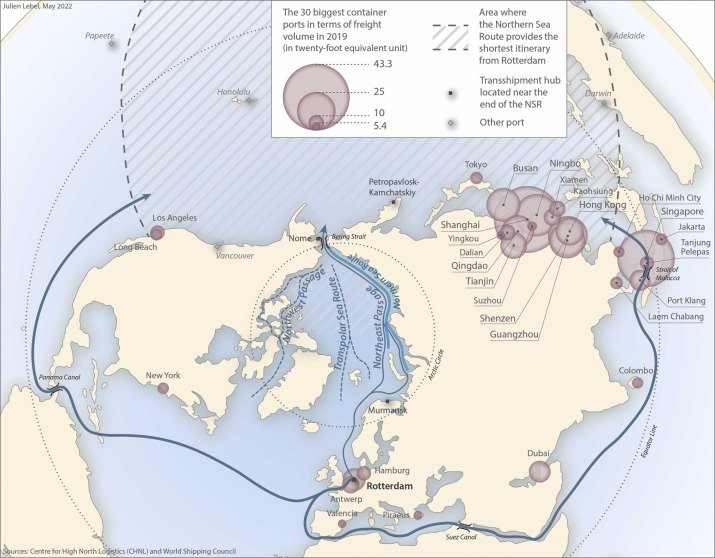

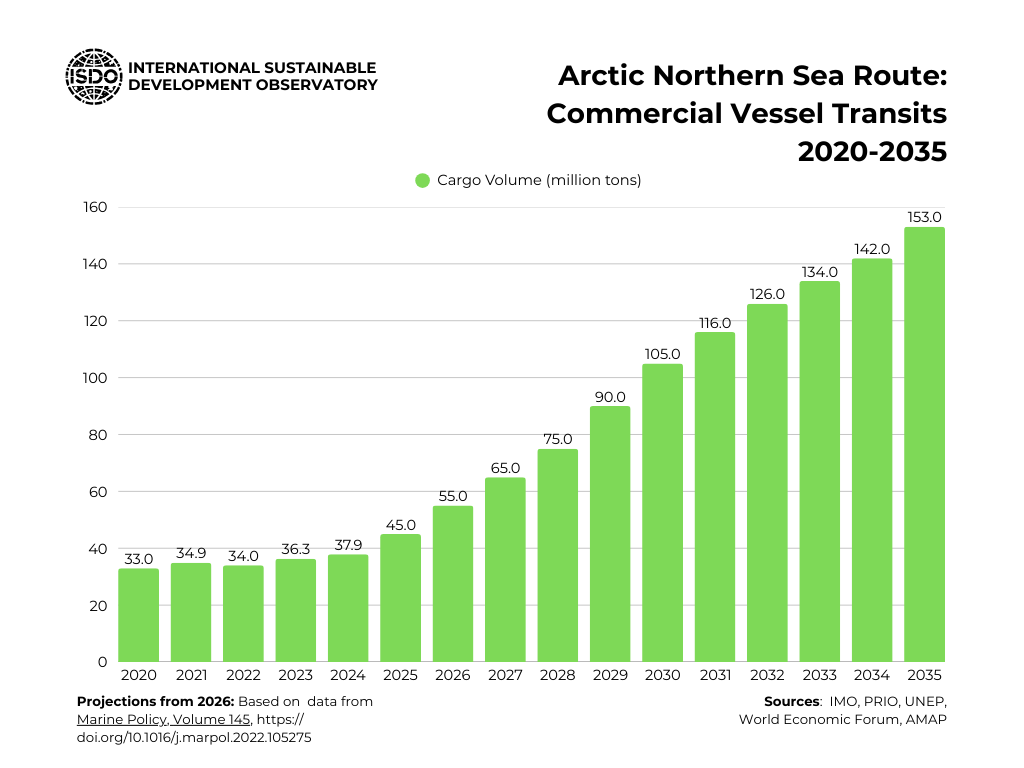

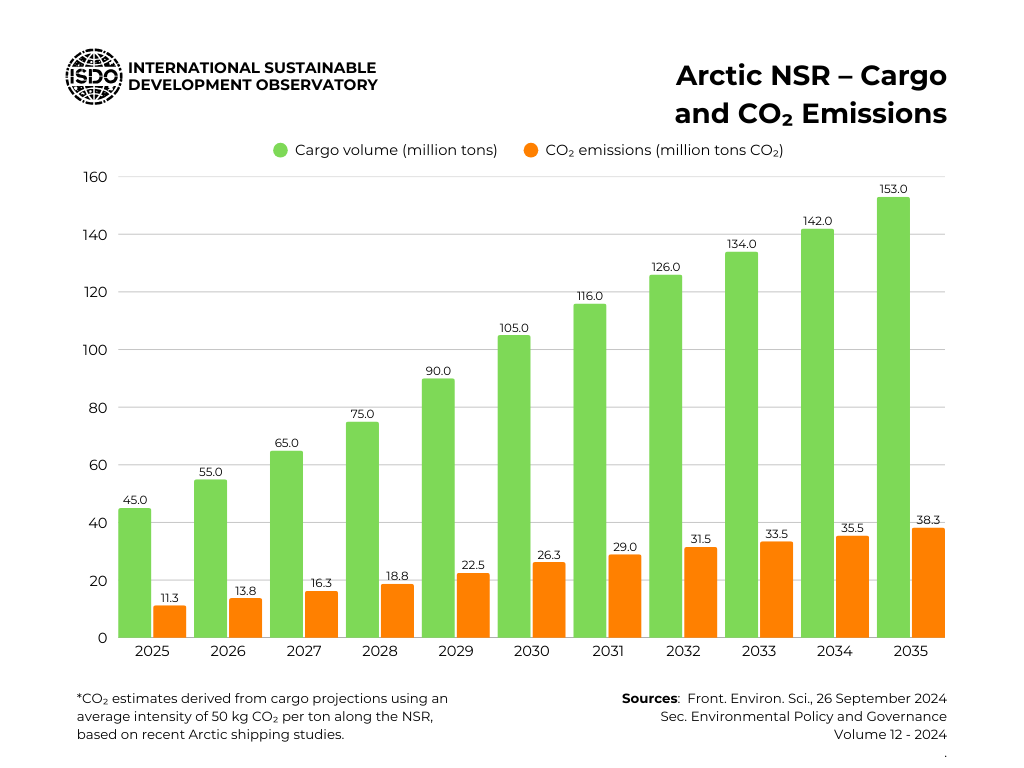

In parallel, climate-driven ice loss is progressively opening the Arctic Sea Route (ASR/NSR), offering up to 30–40% distance reductions on some Europe–Northeast Asia trades. Projections indicate that Arctic routes could handle a non‑trivial share of global traffic by mid‑century and become one of the world’s most carbon‑intensive corridors, particularly for oil, gas and chemical tankers. However, seasonal constraints, high costs, sanctions, and governance gaps limit near-term mainstream adoption. Antarctic and Southern Ocean routes remain largely non‑viable for commercial transit at present, yet climate change, resource pressures, and evolving great‑power competition in the Antarctic Treaty area and Southern Ocean suggest that this maritime frontier will acquire growing geopolitical relevance over the coming decades.

Taken together, these dynamics signal a fragmentation of the global maritime system. Traditional assumptions of open, neutral sea lanes are being eroded by the rise of contested chokepoints, differentiated security architectures, and regionally controlled corridors. The Red Sea crisis illustrates how non‑state actors, embedded in broader regional rivalries and proxy conflicts, can exert outsized influence over global trade flows, with cascading impacts on food security, energy markets, and development trajectories far from the conflict zone.

From a sustainable development perspective, the current re‑routing pattern creates a paradox: risk‑averse route choices aimed at ensuring continuity of trade increase aggregate emissions and environmental pressure, while the gradual opening of polar routes promises shorter distances but shifts carbon and ecological burdens into some of the planet’s most fragile ecosystems. This report argues that maritime geopolitics is now a central dimension of the global sustainability agenda, and that governance responses must simultaneously address security, climate, and development considerations.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

1. The Red Sea Crisis as Maritime Geopolitical Flashpoint

1.1 The Red Sea and Suez in Global Trade Architecture

1.2 Chronology of the Crisis: From 2023 Escalation to 2025 De‑Escalation

1.3 The Houthi Movement: Non‑State Actor, Proxy and Autonomous Player

1.4 Regional Drivers: Iran–Israel Confrontation, Yemen War, Gaza Conflict

1.5 Quantifying the Disruption: Traffic, Costs and Freight Rate Dynamics

2. Restructuring Global Shipping Networks

2.1 The Cape of Good Hope Detour: From Emergency Response to New Baseline

2.2 Dual‑Route Equilibria: Risk, Insurance and Carrier Strategies

2.3 Port and Corridor Winners and Losers in Africa, Europe and Asia

2.4 Implications for Supply Chain Resilience and Lead Times

3. Emerging Polar and Southern Maritime Frontiers

3.1 The Arctic Sea Route: Climate Openings, Constraints and Commercial Prospects

3.2 Geopolitics in the Arctic: Russia, China and Western Responses

3.3 The Southern Ocean and Antarctica: Governance, Resources and Maritime Access

3.4 From Red Sea to Polar Seas: Interconnected Theatres of Maritime Competition

4. Maritime Geopolitics and the International Order

4.1 From Open Seas to Contested Corridors: Bab el‑Mandeb, Hormuz, Malacca, Panama

4.2 Naval Presence, Security Architectures and the Risk of Incident Escalation

4.3 Fragmentation of Global Maritime Governance: IMO, UNCLOS and Regional Regimes

4.4 Implications for Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States

5. Sustainability, Climate and Environmental Justice

5.1 Emissions Impacts of Rerouting: Cape, Suez and Emerging Polar Corridors

5.2 Environmental Risks in Polar and Southern Oceans

5.3 Maritime Disruptions, Food Security and Inequality

5.4 Integrating Maritime Geopolitics into the Sustainable Development Agenda

6. Scenarios for 2030–2050

6.1 Scenario A: Managed Stabilisation and Partial Recentralisation via Suez

6.2 Scenario B: Enduring Fragmentation and Regionalised Maritime Blocs

6.3 Scenario C: Polar Corridors and a Three‑Route Global System

6.4 Stress‑Testing Global Supply Chains Under Each Scenario

7. Policy and Governance Recommendations

7.1 Building a Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean Security Architecture

7.2 Strengthening Global and Regional Maritime Governance

7.3 Aligning Shipping Decarbonisation with Route and Security Choices

7.4 Supporting Vulnerable Coastal and Port States

8. References

1: The Red Sea Crisis as Maritime Geopolitical Flashpoint

Preliminary Situation Description for Section

Yemen’s Geographic and Strategic Position

Geographical Foundations

The Republic of Yemen occupies a critical position at the southern terminus of the Arabian Peninsula, controlling one of the world’s most vital maritime chokepoints. Bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the east, Yemen’s western and southern coastlines extend along the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Arabian Sea, creating a 1,900-kilometer maritime frontier of extraordinary geopolitical consequence.

The nation’s strategic value derives fundamentally from its territorial dominion over the Bab el-Mandeb Strait—a narrowly constrained waterway separating the Arabian Peninsula from the Horn of Africa (Djibouti and Eritrea) by only 26–32 kilometers at its widest point, and a mere 3–22 kilometers across its two navigable channels. This strait represents the sole direct maritime access connecting the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean via the Gulf of Aden, functioning as the southern gateway to the Suez Canal and, by extension, to the Mediterranean Sea and European ports.

Yemen’s geographic advantage is further magnified by its extensive archipelago of approximately 186 islands distributed across the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Arabian Sea. The most strategically significant of these are Perim Island (Arabic: Mayun), positioned at the precise entrance of the Red Sea within the Bab el-Mandeb Strait at coordinates approximately 12°35′N 43°20′E; and the Hanish Islands, Zuqar, Kamaran, and Socotra, which collectively extend Yemen’s territorial reach and surveillance capabilities deep into maritime chokepoint zones.

Maritime Trade Significance

The Bab el-Mandeb Strait’s economic weight cannot be overstated. Approximately 10–12% of global maritime trade—measured in both cargo tonnage and value—transits this narrow passage annually, making closure or significant disruption economically catastrophic at the global level. This traffic includes:

- Petroleum exports: Between 8.7 and 9.2 million barrels per day of crude oil and refined products originating in the Persian Gulf, destined for European, American, and Asian markets. In 2023, this represented approximately 9% of global oil demand.

- Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG): Substantial volumes of LNG from Middle Eastern suppliers, accounting for a significant fraction of global LNG trade.

- Manufactured goods: Electronics, vehicles, textiles, and industrial components transiting between Asian producers and European/American consumers.

- Agricultural products: Wheat, rice, sugar, and other commodities traded between Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

The economic consequence of any disruption is severe: a hypothetical complete closure of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait would force a reroute equivalent to the entire Cape of Good Hope diversion (adding 3,000–4,000 additional nautical miles per journey), multiplying transit times and shipping costs for all affected cargo. The precedent of the 2021 Suez Canal blockage—a six-day grounding of the Ever Given—resulted in global losses estimated at $9 billion per day, demonstrating the acute vulnerability of Middle Eastern trade corridors.

Historical Development and Internal Dynamics (1990–2014)

Post-Cold War State Formation

Following the unification of North and South Yemen in 1990, the Yemeni state emerged as a fragile polity beset by centrifugal pressures. Governance authority remained concentrated in the capital, Sanaa, in the northwestern highlands, while peripheral regions—particularly the tribal-governed southeastern governorates and the cosmopolitan southern port city of Aden—maintained semi-autonomous power structures. The state’s revenue capacity remained fundamentally dependent on oil exports and port rents, both of which experienced volatility during the 1990s and 2000s.

Internally, Yemen’s political identity was structured along overlapping fault lines: the Sunni-Shia sectarian divide (with a substantial Shiite Zaidi population concentrated in the northwest and significant Sunni populations, primarily Shafi’i and Salafi, in central and southern regions); tribal-territorial divisions (with powerful tribal confederations maintaining autonomous military and political authority); and urban-rural economic disparities (with Sanaa and Aden serving as cosmopolitan centers while rural highland and desert regions remained economically marginalized).

The Houthi Movement: Origins and Rise (2004–2014)

The Houthi movement emerged in the early 2000s as a regional insurgency originating in the northwestern Saada Governorate, home to Yemen’s significant Zaidi Shia population. Founded by Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi (killed in 2004) and subsequently led by his brother Abdulmalik al-Houthi, the movement began as a localized rebellion against the Yemeni government’s perceived marginalization of Zaidi Shia interests and alleged collaboration with Sunni Salafi movements and Western powers.

Between 2004 and 2010, the Yemeni government conducted six rounds of military operations against the Houthis in what became known as the “Saada Wars,” causing widespread civilian displacement and strengthening Houthi societal legitimacy as defenders of Shia grievances. Critically, during this period, reports emerged suggesting Iranian support for Houthi forces—though direct Iranian military involvement remained limited and the extent of Iranian financial and logistical support remains contested among scholars.

The Houthis’ political narrative shifted significantly from purely sectarian grievances toward broader populist and anti-Western positioning, particularly following the 2003 invasion of Iraq (perceived as American imperialism targeting the Muslim world) and the U.S. drone campaign initiated in Yemen in 2002. This reframing allowed the movement to extend its appeal beyond Shia constituencies to include nationalist and anti-interventionist Sunni elements, particularly among educated youth and civil society affected by Yemen’s economic stagnation.

State Collapse and Civil War (2014–Present)

The 2015 Houthi Seizure of Power

In September 2014, following weeks of street protests against President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi’s administration—which had implemented unpopular austerity measures including cuts to fuel subsidies—Houthi forces conducted a military offensive northward from their Saada stronghold. On September 21, 2014, Houthis captured Sanaa, the capital, in a swift operation that exposed the fragility of state institutions and the Hadi government’s military weakness.

The Houthi takeover proceeded in stages. By early 2015, Houthi forces:

- Dissolved the Yemeni parliament and established a Supreme Revolutionary Committee to govern the country.

- Forced President Hadi to flee to Saudi Arabia.

- Consolidated control over the northwestern and central regions, including Yemen’s most populous areas.

- Formed a strategic alliance with forces loyal to Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yemen’s former president (1978–2012), who had been marginalized under Hadi’s administration.

This coalition of Houthis + Saleh loyalists effectively controlled Yemen’s state apparatus, including government ministries, the central bank, and significant segments of the military establishment.

The Saudi-Led Intervention and Proxy Conflict Dynamics

Responding to Hadi’s request for external military support, on March 25–26, 2015, a coalition of Arab states led by Saudi Arabia launched “Operation Decisive Storm,” initiating a sustained military campaign of air strikes, naval blockade, and ground operations intended to restore the Hadi government and roll back Houthi control.

The coalition, formally endorsed by the Gulf Cooperation Council (with the notable exception of Oman, which sought a neutral mediation role), included:

- Saudi Arabia (military command and financing)

- United Arab Emirates (ground troops and tactical coordination)

- Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Bahrain, Sudan, and Kuwait (supporting air and naval operations)

- The United States (provision of intelligence, refueling support, and limited military coordination)

However, the conflict quickly transformed into a proxy struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran for regional hegemony. While official Iranian military intervention remained limited, Iran provided financial support, training, and advanced weaponry (including drones, anti-ship missiles, and ballistic missiles) to Houthi forces. The Houthis, in turn, adopted increasingly sophisticated military capabilities and began framing their resistance not merely as local self-determination but as part of a broader Islamic Resistance Axis opposing U.S. hegemony and Israeli actions in the region—rhetoric particularly amplified following the October 2023 Hamas-Israel conflict.

Humanitarian Collapse and Stalemate (2015–2024)

Despite initial Saudi-led coalition successes in retaking southern Yemen (including the strategic port city of Aden in July 2015), military operations failed to dislodge Houthi forces from the northwest, particularly Sanaa and surrounding governorates. Prolonged air strikes killed thousands of civilians and devastated civilian infrastructure—hospitals, schools, power plants, and water systems—without significantly weakening Houthi military capacity or resolve.

By 2016, Yemen had descended into one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises:

- Approximately 80% of Yemen’s population (24+ million people) became displaced, food-insecure, or dependent on humanitarian assistance.

- Cholera and other waterborne diseases proliferated due to collapse of sanitation infrastructure and contaminated water supplies; by 2020, Yemen had experienced multiple cholera outbreaks affecting hundreds of thousands.

- Malnutrition rates among children exceeded 45% in some governorates.

- An estimated 380,000 excess deaths occurred between 2015 and 2021 attributable to the conflict, starvation, and disease, according to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement Credibility Initiative.

Following UN-mediated negotiations initiated in December 2015, a series of temporary ceasefires were implemented (notably 2018–2019 and 2022–2023), reducing active combat intensity but failing to achieve political settlement. The conflict has devolved into a grinding stalemate characterized by:

- Houthi control of the northwestern governorates (Sanaa, Saada, Amran, Dhamar, and surrounding areas), home to approximately 70% of Yemen’s population.

- Saudi-aligned and UAE-backed forces controlling southern and eastern Yemen, fragmented among multiple factions including the internationally recognized government, the Southern Transitional Council (a separatist entity backed by the UAE), and various tribal militias.

- Persistent Houthi military attacks against Saudi infrastructure, regional shipping, and other strategic targets.

Internal Fragmentation and Competing Centers of Power

A crucial aspect of the contemporary Yemeni conflict is its transformation into a multi-sided struggle rather than a binary Houthi-government confrontation. Key actors now include:

1. The Houthis (Ansar Allah): The de facto state authority in northwestern Yemen, with hierarchical military and political structures controlled by the al-Houthi family (particularly Abdulmalik al-Houthi). Their organization includes both conventional military forces and asymmetric capabilities (drone production, missile manufacturing, naval operations).

2. The Internationally Recognized Government (IRG): Formally led by President Hadi, physically based in Saudi Arabia and in Aden, commanding fragmented military forces and lacking domestic legitimacy in many southern and eastern regions.

3. The Southern Transitional Council (STC): An explicitly separatist movement seeking southern Yemen independence, backed militarily and financially by the UAE. The STC has engaged in direct military conflict against both Houthi forces and the IRG, capturing strategic cities including Aden (temporarily in 2019–2024).

4. Tribal and Regional Militias: Dozens of armed groups controlled by local tribal leaders, each pursuing parochial interests and shifting allegiances based on tactical advantage.

This fragmentation means that even a hypothetical Houthi-Saudi agreement would not necessarily produce state reconstruction, as control of southern territory remains contested among multiple incompatible factions.

Yemen’s Strategic Geography and the Bab el-Mandeb: Why Control Matters

The geographic positioning of Yemen within the Bab el-Mandeb Strait creates a unique military-strategic asymmetry. While Yemen itself possesses minimal conventional military capacity (no functioning navy, limited air force, and economically devastated defense infrastructure), its coastal dominance of the strait provides access to globally critical maritime lanes with minimal technical barriers to interdiction.

Narrow Bottleneck Geometry

The Bab el-Mandeb’s narrowness creates fundamental geographic constraints on maritime traffic. The strait is divided by Perim Island (Yemen’s possession) into two channels:

- The eastern channel (between Perim and Yemen’s mainland coast): approximately 3 kilometers wide, with average depth 20–30 meters—unsuitable for large tankers and avoided by most international traffic.

- The western channel (between Perim and Djibouti/Eritrea): approximately 22 kilometers wide, with depth approximately 280 meters—the practical maritime corridor for large vessels.

For large ships, tankers, and especially supertankers carrying oil and LNG, the western channel is effectively the only usable route. This creates a geography of vulnerability: any actor capable of threatening shipping in a 22-kilometer-wide corridor can impose significant costs on global commerce without requiring control of the entire strait or military parity with defending powers.

Houthi Asymmetric Naval Capabilities

Beginning in 2016–2017, Houthi forces developed asymmetric maritime strike capabilities including:

- Unmanned aerial vehicles (drones): Initially surveillance/reconnaissance platforms, progressively weaponized with explosives to attack regional targets and vessels.

- Fast attack craft: Modified speedboats equipped with explosives, used for suicide attacks and harassment operations.

- Anti-ship cruise missiles: Developed indigenous or supplied by Iran, including the Houthi C-802 derivative, capable of threatening large commercial vessels and military ships at ranges exceeding 100 kilometers.

- Naval mines and underwater obstacles: Deployed to restrict navigation corridors.

Critically, these capabilities require no conventional naval fleet, no air force, and no significant power projection capacity—only presence in coastal areas Yemen already controls and technical capability to operate relatively inexpensive weapons systems. This creates the geographic paradox: a militarily weak state, devastated economically, controls a chokepoint that can constrain global commerce.

Yemen in the Broader Regional Security Complex

Yemen’s instability and the Houthi movement’s rise cannot be isolated from the broader regional security architecture of the Middle East. The conflict instantiates several intersecting dynamics:

1. Saudi-Iranian Regional Competition: Yemen has become the primary arena of Saudi-Iranian proxy competition, as both regional powers seek to deny the other’s sphere of influence and assert hegemonic claims over the Arabian Peninsula and surrounding maritime zones.

2. Great Power Strategic Interests: The United States, China, Russia, and European powers maintain strategic interests in Red Sea security, trade route protection, and regional geopolitical positioning, leading to varying degrees of military and diplomatic involvement.

3. Sectarian-Nationalist Ambiguity: While the Houthi movement is characterized as a Shia insurgency with Iranian links, it has increasingly adopted nationalist and anti-Western framing that appeals beyond sectarian constituencies, complicating efforts to categorize the conflict as purely sectarian or as Iranian proxy warfare.

4. State Failure and Humanitarian Spillovers: Yemen’s collapse as a functional state has created ungoverned spaces conducive to transnational extremist organizations (Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, ISIS affiliates), human trafficking networks, and regional refugee flows that destabilize neighboring countries including Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, and Oman.

Implications for Maritime Security and Global Trade

The convergence of Yemen’s geographic control of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, the Houthi movement’s asymmetric capabilities, and the broader regional conflict dynamic creates a novel form of maritime vulnerability wherein a non-state actor with limited conventional military power can nonetheless impose significant constraints on global trade, energy security, and supply chain continuity.

This situation represents a fundamental challenge to the post-Cold War international order’s assumptions about maritime security, wherein great-power navies (notably the U.S. Navy) were presumed capable of guaranteeing freedom of navigation through critical chokepoints. The Houthi attacks on shipping beginning in November 2023—discussed in detail in Section 1.3 of the main report—demonstrate both the potency and the limitations of this geographic vulnerability: while Houthis lack power to permanently close the strait, they possess sufficient capability to impose costs (in risk premiums, rerouting, and delays) that fundamentally alter global shipping economics and supply chain resilience.

1.1 The Red Sea and Suez in Global Trade Architecture

The Red Sea, together with the Suez Canal and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, represents one of the world’s most strategically critical maritime corridors. Approximately 12–15% of global maritime trade by volume transits this chokepoint annually, with particularly high concentrations in containerized cargo—estimates place Red Sea container shipping at approximately 30% of global container traffic.

This extraordinary centrality reflects the corridor’s fundamental role as the shortest and fastest maritime route linking Europe and Asia, bypassing circumnavigation around Africa. For shipping companies, the choice is stark: traverse the Red Sea and Suez Canal in approximately 14 days (Asia to Europe), or reroute around the Cape of Good Hope over 21–24 days. This speed advantage translates directly into operational cost savings, inventory efficiency, and competitive advantage in time-sensitive markets.

Beyond raw trade volumes, the Red Sea corridor carries commodities essential to global food security, energy markets, and manufacturing supply chains:

- Rice exports: Approximately 20% of global rice exports transit the Red Sea, predominantly from Asia to Africa and the Middle East, underpinning food security for over 1 billion people in sub-Saharan Africa and developing Asia.

- Wheat and grain: Approximately 15% of global wheat exports flow through Bab el-Mandeb, primarily sourced from Eastern Europe and destined for Middle Eastern, African, and Asian markets.

- Crude oil and refined products: The Red Sea carries an estimated 8.6 million barrels per day of Persian Gulf crude oil destined for Europe, with significant flows to Asia via alternative routings.

- Liquefied natural gas (LNG): Qatar and other Gulf producers ship LNG through the corridor to Europe and increasingly to Asia, with critical importance for European energy security given Russian supply constraints post-2022.

- Containerized cargo: High-value electronics, pharmaceuticals, machinery, and manufactured goods worth hundreds of billions of dollars annually flow through Red Sea container services.

For Egypt, the Suez Canal Authority represents an irreplaceable source of foreign currency revenue, generating approximately $6 billion annually before the recent crisis. For a nation with persistent fiscal vulnerabilities, foreign exchange constraints, and development funding pressures, this revenue stream is not peripheral but central to national economic stability. In 2024, Suez Canal revenues declined precipitously as traffic diverted, creating immediate fiscal pressure on the Egyptian government.

The geographical configuration creates a “natural monopoly” in routing. The Bab el-Mandeb Strait narrows to only 30 kilometers at its narrowest point, and the Suez Canal traverses Egyptian sovereign territory, placing the corridor under singular state control. Combined with the technical requirements of canal transit (pilots, passage fees, scheduling), this creates an assumed underlying two centuries of global trade: that the Red Sea–Suez corridor would remain open, neutral, and accessible to all flags and operators under international maritime law.

This assumption proved fragile beginning in November 2023.

1.2 Chronology of the Crisis: From 2023 Escalation to 2025 De-Escalation

Phase 1: Rapid Escalation and Network Collapse (November 2023–February 2024)

The Houthi attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea began in mid-October 2023 but escalated dramatically from late November 2023 onwards. The first significant attack occurred on October 19, 2023, against the M/V Galaxy Leader, a vehicle carrier operated by Israeli-linked companies. By early 2024, Houthi attacks had become systematic and frequent, with multiple strikes weekly against container ships, tankers, and general cargo vessels in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and Red Sea proper, regardless of flag or cargo destination.

The Houthis explicitly stated their operational rationale: solidarity with Palestinian civilians affected by the Israeli military campaign in Gaza (initiated October 7, 2023), and opposition to perceived U.S. and Israeli regional hegemony. By October 2024, the Houthis had conducted over 190 maritime attacks, demonstrating sustained operational capability and evolving attack sophistication, including use of ballistic missiles, anti-ship cruise missiles, suicide drones, and remotely operated naval vessels.

The immediate impact on shipping networks was catastrophic. Daily vessel transits through the Bab el-Mandeb Strait collapsed from an average of approximately 70 merchant ships per day (2023 baseline) to roughly 35 per day by early 2024—a 50% reduction in volume. Container shipping experienced even sharper declines, with 90% collapse in Suez Canal container transits between December 2023 and March 2024. Overall Red Sea traffic declined by 57.5%, from an average daily volume of 4.0 million metric tons in late 2023 to approximately 1.7 million metric tons by early 2024.

Shipping companies, confronted with insurance surcharges, heightened risk premiums, potential vessel damage, and crew safety concerns, made rapid strategic decisions. The alternative routing around the Cape of Good Hope surged by an estimated 74% above prior-year levels in early 2024. This represented not merely temporary diversion but a structural shift, as the alternative route added 6,000–11,000 nautical miles to Asia–Europe voyages and extended transit times by 10–14 days, directly increasing per-ship fuel consumption costs by approximately $1 million per voyage.

Phase 2: Stabilized Disruption and Tentative Recovery (March 2024–September 2025)

From March 2024 onwards, despite U.S. and coalition military interventions against Houthi capabilities (including airstrikes on Houthi command centers, weapons depots, and launch facilities), attacks did not cease but rather entered a pattern of sporadic operations. While attack frequency diminished somewhat compared to the January–February 2024 peak, the threat perception remained sufficiently credible to sustain rerouting behavior among risk-averse shipping operators.

During this extended period, Red Sea traffic remained persistently suppressed at 35–40% of pre-crisis baselines. Insurance risk premiums remained elevated, particularly for Red Sea transits, and major shipping operators—including MSC, CMA CGM, and Maersk—maintained mixed or cautious policies on Red Sea routing. While some carriers conducted trial transits through the Suez Canal, particularly after periods of reduced attack activity, broad-based confidence restoration remained elusive.

The economic costs of prolonged disruption accumulated. Shipping companies operating on thin profit margins (typically 2–5% net margins pre-crisis) absorbed higher fuel costs from longer voyages, sustained insurance surcharges, and operational complexity. For time-sensitive commodities—fresh produce, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, e-commerce goods—the extended transit times created substantial losses as perishable goods spoiled, contract deadlines were missed, and just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing schedules were disrupted.

Global inflation dynamics were affected. Industry assessments and central bank analyses indicated that container shipping cost increases directly attributable to Red Sea disruption contributed measurably to global inflation in 2024–2025, with particular impact on food prices in vulnerable regions, manufacturing supply costs, and energy markets.

Phase 3: Tentative De-Escalation and Partial Recovery (October 2025–January 2026)

Beginning in October 2025, following the Gaza ceasefire agreement formalized on October 10, 2025, and a Houthi announcement of a pause in maritime attacks, a marked shift occurred in the threat environment. While Houthis did not formally renounce attacks permanently, the operational pause created the first significant window of reduced threat since November 2023.

Suez Canal authorities reported immediate recovery signals. October 2025 saw 229 vessels transit the canal—the highest monthly figure since the crisis began. For the July–October 2025 period, a total of 4,405 ships carrying 185 million metric tons transited the canal, compared to 4,332 vessels with 167.6 million tons during the same period in 2024—representing modest recovery. Egypt’s Suez Canal Authority reported that revenues rose 14.2% year-over-yearbetween July and October 2025, signaling a return of some commercial confidence.

However, as of January 2026, the recovery remains partial and fragile. Red Sea traffic continues at approximately 60% below pre-crisis levels, and Suez Canal transits remain substantially depressed compared to 2023 baselines. Multiple factors explain this persistent suppression despite reduced hostilities:

- Risk Perception vs. Risk Reality Divergence: Shipping companies, having invested in reorganizing logistics networks around the Cape route, exhibit organizational inertia. Reversing these decisions requires sustained confidence that threats are permanently eliminated, not merely temporarily suspended. Given the underlying geopolitical drivers (Gaza conflict, Iran–Israel tensions) remaining unresolved, companies rationally assess the pause as potentially temporary.

- Infrastructure Lock-In and Port Investment: The Cape route and Indian Ocean corridors have attracted infrastructure investment and shipping company partnerships, making them partially self-sustaining. Port congestion in alternative hubs (Singapore, Suez, Port Said), feeder service development, and insurance market adaptation create path-dependent choices that persist even after threat levels decline.

- Persistent Insurance Premium Differential: Even with reduced attack frequency, insurance markets continue charging “war zone” surcharges for Red Sea transit, maintaining a cost differential between the Suez route and the Cape alternative that makes the longer route economically competitive for many operators.

- Underlying Geopolitical Drivers Remain Unresolved: The Hamas–Israeli conflict, Gaza internal terror crisis, and Iran–Israel strategic competition show no signs of fundamental resolution. Shipping companies, rationally, maintain precautionary rerouting as a hedge against renewed escalation.

Current Status: Crisis Transitioned to Structural Disruption (January 2026)

As of January 2026, the Red Sea crisis has entered a paradoxical state: hostilities have not resumed at the intensity of late 2023–early 2024, yet the global shipping network remains substantially reconfigured from pre-crisis patterns. This signals a transition from acute crisis to structural disruption—the Red Sea and Suez Canal no longer function as the seamless, neutral, and assumed-reliable corridor of prior decades.

Instead, the Red Sea has become a conditional route, accessed selectively and with sustained risk premiums. This structural shift has far-reaching implications for global trade costs, supply chain resilience, geopolitical positioning of maritime logistics, and development trajectories for vulnerable economies dependent on maritime trade.

1.3 The Houthi Movement: Non-State Actor, Proxy, and Autonomous Player

Understanding the Red Sea crisis requires sophisticated analysis of the Houthi movement—the non-state actor whose decisions and capabilities have reshaped global maritime commerce. The Houthis are neither a homogeneous puppet force controlled by Iran, nor an independent actor uninfluenced by regional powers. Rather, they represent a complex hybrid entity: a territorial movement with distinct political agenda, a capable military force armed and trained by Iran, and an ideological actor motivated by Zaydi revivalist Islam and anti-hegemonic regionalism.

Historical Origins and Political Development

The Houthi movement, officially known as Ansar Allah (“Helpers of God”), emerged from northern Yemen in the early 1990s as a moderate theological and cultural revival movement. Founded through an organization called “Believing Youth” (BY) in 1992 in Saada Governorate by members of the al-Houthi family—most prominently Hussein al-Houthi—the movement initially focused on religious education, establishing schools and summer camps to promote Zaydi Islamic teachings among Yemen’s Zaydi-majority communities (approximately 25–30% of Yemen’s population).

The movement underwent ideological and operational radicalization in the early 2000s, influenced by the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq and the organizational model of Lebanese Hezbollah. Beginning around 2003, Hussein al-Houthi began incorporating explicitly anti-American and anti-Israel rhetoric into sermons at Al-Saleh Mosque in Sanaa, disseminating the movement’s now-iconic slogan: “God is great, death to America, death to Israel, curse on the Jews, victory to Islam.” This religious positioning attracted government security attention. When Yemen’s President Ali Abdullah Saleh ordered al-Houthi’s arrest in 2003, al-Houthi refused submission and instead initiated an armed insurgency.

Yemeni government forces killed Hussein al-Houthi in September 2004, an event that transformed the movement from theological dissent into a sustained military rebellion. From 2004 to 2010, the Houthis conducted six rounds of major fighting (the “Saada Wars”) against Yemen’s central government, demonstrating organizational capacity, military resilience, and ability to mobilize local constituencies. Following the 2011 Yemeni Revolution and subsequent state collapse, the Houthis expanded territorially and consolidated power over northern Yemen’s most populous regions.

Leadership passed to Hussein al-Houthi’s brother, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, who continues leading the organization today. Under Abdul-Malik’s leadership, the movement evolved from a primarily local and sectarian insurgency into a major regional political-military actor with significant territorial control (approximately 70% of Yemen’s population), explicit geopolitical ambitions, and increasingly sophisticated military capabilities.

Military Capabilities: Evolution and Iranian Support

The Houthi arsenal has evolved substantially from light infantry capabilities to a sophisticated military apparatus spanning ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and unmanned systems.

Early Capabilities (2004–2014): During the initial insurgency phase, the Houthis relied primarily on light infantry tactics and small arms acquired through battlefield captures from Yemeni military forces. As Yemen’s central authority weakened between 2004 and 2010, the Houthis systematically looted military weapons caches, acquiring Scud ballistic missiles and OTR-21 Tochka tactical missiles originally supplied to Yemen during the 1994 civil war.

Iranian Strategic Support (2009–Present): Iranian backing emerged as the critical force multiplier in Houthi military development. While earlier interactions existed, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Forcesubstantially increased military assistance beginning around 2009, accelerating dramatically after the Houthis’ takeover of northern Yemen in 2014–2015. This support included:

- Ballistic and cruise missile components, initially smuggled via maritime vessels to evade detection

- Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technologies, including design plans and technical expertise

- Training and military advisory support through organizations like Hezbollah’s Unit 3800, which has trained Houthi personnel since approximately 2014–2015 in advanced weapon systems operation, naval tactics, and drone technologies.

- Intelligence sharing and target acquisition support through Iranian-flagged vessels positioned in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean to provide maritime surveillance.

Ballistic Missile and Drone Arsenal (2015–2025): From 2015 onwards, the Houthis unveiled an expanding arsenal of ballistic missiles and unmanned systems. By June 2019, the Houthis had launched a cumulative total of 226 ballistic missiles across their insurgency campaign. Drone operations peaked in 2021 with widespread targeting of Saudi oil infrastructure, notably the September 2019 Abqaiq–Khurais attack on Saudi Aramco facilities in eastern Saudi Arabia—while Houthis claimed responsibility, U.S. intelligence initially assessed Iranian direct involvement, though subsequent analysis credits Houthi capability given available training and organizational sophistication.

Naval Warfare Capabilities: Most relevant to the Red Sea crisis is the Houthis’ development of maritime attack systems. From 2015 onwards, the Houthis converted UAE-donated patrol boats into water-borne improvised explosive devices (WBIEDs), producing designs including the Tawfan-1, Tawfan-2, and Tawfan-3 classes capable of autonomous or remote operation with explosive payloads for ramming or detonation alongside larger vessels.

In October 2016, Houthi shore-based anti-ship missiles severely damaged the UAE Navy’s HSV-2 Swift, a hybrid catamaran, forcing its decommissioning. This demonstrated the Houthis’ evolution beyond small-craft tactics to employ sophisticated standoff anti-ship systems.

Most recently, Iran supplied longer-range anti-ship systems including Noor missiles (120 km), Qader missiles (200 km), and Khalij Fars ballistic anti-ship systems (300 km), unveiled during Houthi military parades in 2022–2024. Combined with target acquisition systems including coastal radar installations and intelligence-gathering vessels such as the Iranian-flagged MV Behshad (positioned off Eritrea), the Houthis possess technical apparatus for sustained anti-ship operations across vast Red Sea and Gulf of Aden areas.

Analytical Framework: Houthis as Multiple Actors

The Houthi movement occupies a complex analytical position, simultaneously functioning as:

1. A Strategic Instrument of Iranian Regional Policy: Evidence for Iranian strategic use is substantial. Iran’s provision of weapons, training, and intelligence through Quds Force and IRGC channels is well-documented by U.S. intelligence, UN reporting, and Saudi/UAE assessments. Iranian officials have openly stated their strategic rationale: Houthis serve as Iranian “proxy” force extending Tehran’s regional influence, analogous to Hezbollah’s role in Lebanon. Houthis’ 2023–2024 maritime attacks on commercial shipping aligned with Iranian interests in disrupting Western/Gulf-aligned commerce, elevating oil prices, and demonstrating Iran’s capacity to project power through non-state proxies. The timing—beginning immediately after October 7, 2023, Hamas attacks and Israeli Gaza invasion—suggests at minimum opportunistic coordination with Iranian strategic assessments.

2. An Autonomous Political-Military Actor: Yet characterizing the Houthis as merely Iranian instruments obscures their independent agency and distinct political agenda. The movement emerged from Yemen’s internal Zaydi political marginalization and sectarian dynamics, predating significant Iranian involvement by over a decade. The Houthis have repeatedly resisted Iranian pressure on specific operational decisions, negotiated for autonomy in tactical planning, and pursued political objectives (territorial consolidation, governance institutionalization in northern Yemen, resource control) independent of Tehran’s immediate interests.

The movement has constructed genuine institutional structures—media networks (Almasirah TV, 25+ publications), administrative governance organs in controlled territories, tribal consultation councils—reflecting authentic political consolidation, not merely external puppetry.

3. An Ideologically Motivated Resistance Movement: The Houthis’ framing of Red Sea attacks as “resistance to imperialism” and solidarity with Palestinian civilian victims reflected genuine ideological commitment, not merely cover for Iranian operations. The movement’s use of traditional Yemeni oral poetry (zawamil) infused with Houthi messaging, disseminated via social media, generated authentic grassroots mobilization resonating with constituencies beyond Iranian prompting.

Conclusion: The Houthis as Drivers of the Crisis

The Houthis’ decision to attack commercial shipping from November 2023 onwards reflects:

- Opportunistic alignment with Iranian strategic interests in disrupting global trade

- Autonomous political-military agency pursuing territorial and regional consolidation

- Ideological commitment to Palestinian solidarity and opposition to perceived U.S./Israeli hegemony

- Tactical calculation that maritime attacks impose costs on Israel’s strategic partners

- Demonstration of capability and deterrence signaling to rival Yemen factions and regional adversaries

This multiplicity of motivations explains the complexity: there is no single “off switch” for resolving the crisis. Military strikes on Houthi capabilities damage their arsenal but do not address underlying grievances or incentives. Iranian weapons provision continues even under military pressure. Addressing Palestinian–Israeli conflicts alone would not necessarily eliminate Houthi maritime operations, since these operations serve multiple strategic purposes for multiple actors.

1.4 Regional Drivers: Iran–Israel Confrontation, Yemen War, Gaza Conflict

The Red Sea crisis cannot be understood as an isolated maritime security incident. Rather, it emerges from a complex matrix of regional geopolitical tensions, proxy warfare dynamics, and unresolved conflicts spanning the Levant, Persian Gulf, and Arabian Peninsula. Three primary regional drivers structure the geopolitical environment enabling Houthi attacks:

The Iran–Israel Strategic Competition (2023–2025)

The broader Iran–Israel strategic confrontation, which intensified dramatically following the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack on Israel and Israel’s subsequent Gaza military campaign, provided the immediate geopolitical context enabling Houthi Red Sea operations.

The October 7, 2023 attack on Israeli territory, in which Hamas militants killed approximately 1,200 Israeli civilians and soldiers and captured roughly 240 hostages, triggered Israel’s military response: a sustained bombardment and ground invasion of Gaza that, by January 2026, had resulted in over 40,000 Palestinian deaths, widespread destruction of civilian infrastructure, and a humanitarian catastrophe characterized by acute food insecurity, disease outbreak risk, and psychological trauma affecting 2.3 million Palestinians.

The Gaza war, framed by Israel as necessary counterterrorism and by the Houthis and Iran as colonialism and genocide, became the explicit justification for Houthi maritime attacks. Houthi leadership, including Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, issued statements explicitly linking Red Sea attacks to Palestinian solidarity and opposition to Israeli military operations. This framing resonated throughout the Arab and Muslim world, generating grassroots support that extended beyond Iran’s direct strategic influence.

The Iran–Israel dimension intensified further with direct state-to-state escalation in April 2024 and again throughout 2024–2025. On April 14, 2024, Iran launched approximately 300 ballistic and cruise missiles and drones at Israeli territory in direct retaliation for the February 2024 Israeli airstrike on the Iranian embassy compound in Damascus (which killed senior IRGC general Mohammad Reza Zahedi). While Israel’s air defenses intercepted most missiles, the April 2024 attack represented unprecedented direct Iranian retaliation, marking a qualitative shift toward state-to-state confrontation.

Israel responded in kind, conducting airstrikes against Iranian military targets, including air defense systems and strategic assets. By late 2024–early 2025, the Iran–Israel strategic competition had evolved into a complex multi-front confrontation encompassing direct attacks, proxy warfare, cyber operations, and sanctions escalation. This strategic escalation created an environment in which Iran’s support for proxy forces (including the Houthis) became more strategically important as a means of imposing costs on U.S.-allied actors.

The Yemen Civil War as Proxy Battlefield (2014–Present)

The Houthi maritime attacks must be situated within the broader context of Yemen’s protracted civil war, which has been characterized as a proxy conflict between Saudi Arabia (backed by the United Arab Emirates and Western powers) and Iran.

Yemen’s civil war emerged from the collapse of Yemen’s weak central state, longstanding sectarian tensions between Sunni-majority and Zaydi Shia-plurality communities, and competing regional power interests. In 2014–2015, the Houthis consolidated control over northern Yemen (including the capital Sanaa) and much of the country’s most populous regions. Saudi Arabia, perceiving the Houthi advance as an extension of Iranian regional expansion, launched a military intervention in March 2015 with a coalition of Arab allies and Western logistical support.

The resulting war, described as among the world’s worst humanitarian crises, has killed approximately 300,000 Yemenis (directly and indirectly), displaced millions, and created widespread acute food insecurity affecting over 80% of Yemen’s population as of 2023–2025. The war has also destroyed Yemen’s central state capacity, educational and health infrastructure, and economic institutions, creating a de facto partition of Yemen into Houthi-controlled northern territories, internationally recognized government-controlled southern and eastern areas (backed variously by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other factions), and contested zones.

For Iran, the Houthi-controlled northern Yemen represents a valuable asset in its broader regional strategy: the Houthis provide Tehran with a foothold on the Arabian Peninsula, strategic leverage against Saudi Arabia (a regional rival), and a proxy force capable of imposing costs on Western and Gulf-aligned interests without direct Iranian military commitment. Iran’s military support to the Houthis, estimated at hundreds of millions of dollars annually, is a cost-effective investment in regional influence. For Saudi Arabia and the UAE, conversely, the Yemen conflict represents an existential regional security concern: preventing Iranian consolidation of power on the Arabian Peninsula’s southern flank.

The Yemen civil war has thus become embedded in the broader Saudi Arabia–Iran rivalry, which extends from Iraq and Syria through Lebanon. This Saudi–Iran proxy warfare dynamic underlies not only the Houthi attacks but also the regional fragmentation affecting global maritime commerce.

The Gaza Humanitarian Crisis as Ideological Catalyst (October 2023–Present)

The Gaza war, triggered by the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack, provided the immediate ideological and political catalyst for Houthi maritime escalation. While Iran’s strategic interests in disrupting global commerce and elevating costs for the U.S./Israeli alliance were evident, the Houthis’ explicit framing of Red Sea attacks as “solidarity with Palestinians” reflected genuine ideological motivation rooted in Zaydi Islamic anti-imperialism and pan-Islamic solidarity narratives.

The Gaza humanitarian crisis acquired particular salience in Arab and Islamic constituencies by late 2023–early 2024. As the Israeli military campaign progressed, civilian casualties mounted, and humanitarian conditions deteriorated (with acute food insecurity, disease risks, and displacement of civilian populations). International humanitarian organizations (in many cases questioned for their lack of neutrality and for having members linked to terrorism) including the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and Doctors Without Borders documented supposed systematic destruction of civilian infrastructure, denial of humanitarian assistance, and conditions approaching famine in parts of Gaza. Something that was used to glorify the attacks rather than to curb collateral damage in the conflict, constituting a violation of the IHL.

For the Houthis, this humanitarian catastrophe provided a powerful legitimizing narrative for Red Sea operations. Unlike abstract anti-imperialism, the Palestinian issue resonates with deep emotional and religious significance throughout Muslim-majority societies. Houthi framing of the Red Sea attacks as “resistance” to Israeli expansion and U.S. hegemony generated grassroots support within Yemen and broader Arab constituencies that transcended Iran’s strategic interests.

This ideological dimension explains why military defeats of Houthi capability (through U.S./coalition airstrikes) and pauses in Iranian resupply have not eliminated Red Sea attacks: the movement possesses autonomous motivation distinct from Iranian strategic direction. Equally, it explains why the Gaza ceasefire negotiated in October 2025 led to a Houthi operational pause—when the immediate humanitarian crisis receded somewhat, the primary ideological justification for attacks weakened.

Synthesis: Interconnected Regional Drivers

The Red Sea crisis emerges from the intersection of these three regional dynamics:

- Iran–Israel strategic competition provides structural incentive for disruption of global commerce benefiting Western/Allied actors

- Yemen’s protracted civil war provides organizational infrastructure and territorial control enabling Houthi maritime operations

- Gaza humanitarian crisis provides ideological legitimacy and grassroots mobilization fuel for attacks

These three drivers are not independent but rather reinforcing. Iran’s strategic interests align with genuine Houthi autonomy and grassroots Arab sentiment regarding Palestine. Yemen’s territorial fragmentation enables Houthi operational independence. The Gaza crisis provides real humanitarian justification transcending proxy warfare reductionism.

This synthesis explains why the Red Sea crisis is not a simple puzzle with a single solution. Addressing one driver alone—through military pressure on Houthis, diplomatic intervention in Yemen, or ceasefire agreements regarding Gaza—proves insufficient without simultaneously addressing the others.

1.5 Quantifying the Disruption: Traffic, Costs and Freight Rate Dynamics

The Red Sea crisis, while politically and geopolitically significant, is perhaps most dramatically illustrated through quantitative analysis of shipping volumes, freight rates, and operational costs. These metrics translate abstract geopolitical analysis into concrete economic impacts affecting supply chains, inflation, and development trajectories globally.

Shipping Volume Collapse and Recovery

Phase 1 (November 2023–February 2024): Acute Disruption

The immediate impact of Houthi attacks on shipping volumes was severe and near-total:

- Bab el-Mandeb daily transits: Collapsed from ~70 vessels/day (pre-crisis baseline) to ~35 vessels/day (50% reduction)

- Red Sea overall traffic: Declined 57.5%, from 4.0 million metric tons/day to 1.7 million metric tons/day

- Suez Canal container transits: Experienced 90% decline between December 2023 and March 2024

- Cape of Good Hope traffic: Surged 74% above prior-year levels as diversions accelerated

These volume contractions were not gradual declines but rather sharp cliff-edge collapses, reflecting the immediate risk reassessment by shipping operators following the first coordinated Houthi attacks.

Phase 2 (March 2024–September 2025): Stabilized Suppression

During this extended period, Red Sea traffic remained persistently suppressed at 35–40% of pre-crisis baselinesdespite reduced attack frequency. This “sticky” suppression—failure to recover despite reduced threats—illustrates the importance of sustained confidence in maritime security. Shipping operators, having reorganized logistics networks and supply chains around the Cape route, did not immediately reverse course:

- Suez Canal monthly transits: By October 2025 (after the Gaza ceasefire), monthly transits reached 229 vessels—described as the “highest monthly figure since the crisis began,” yet still representing suppressed overall volumes compared to 2023

- Red Sea traffic: Remained at approximately 60% below pre-crisis levels as of January 2026

- Cape of Good Hope: Maintained elevated traffic levels, absorbing rerouted commerce

Phase 3 (October 2025–January 2026): Tentative Recovery with Persistent Suppression

The October 2025 Gaza ceasefire and Houthi announcement of an operational pause created the first significant uptick in Red Sea transits since the crisis began:

- Suez Canal revenues: Rose 14.2% year-over-year between July–October 2025

- Monthly vessel transits: Increased to 229 in October 2025

- Quarterly volumes (July–October 2025): 4,405 vessels carrying 185 million metric tons, compared to 4,332 vessels with 167.6 million tons during the same period in 2024

However, even this recovery remained modest. Red Sea traffic in January 2026 continued at approximately 60% below pre-crisis levels, demonstrating that partial threat reduction is insufficient to restore full shipping confidence.

Freight Rate Dynamics: The Financial Impact

The disruption of shipping volumes directly translated into elevated freight rates across major trade routes, with Asia–Europe and Asia–Mediterranean routes experiencing the most dramatic increases:

Phase 1 (December 2023–July 2024): Rate Spike

From the onset of disruptions through the summer peak season of 2024, container freight rates experienced historic spikes:

- Shanghai to Rotterdam (Asia–Europe): Rates tripled from typical $1,500–1,700/FEU (20-foot equivalent unit) pre-crisis to $5,500/FEU by February 2024; peaked at $8,400/FEU in July 2024

- Shanghai to Mediterranean: Rates more than tripled, reaching approximately $6,500/FEU by mid-2024

- Shanghai to U.S. West Coast: Rates increased to $3,715/FEU, 49% above pre-Red Sea crisis levels of $2,500/FEU

- Shanghai to U.S. East Coast: Similar increases, with rates reaching $3,000/FEU

These rate increases reflected not only the direct cost of rerouting (longer distance, additional fuel) but also the scarcity of vessel capacity. As vessels were absorbed into longer-distance Cape routing, the available capacity for traditional routes contracted sharply, creating a capacity shortage that dramatically elevated rates.

Phase 2 (August 2024–September 2025): Rate Normalization with Elevated Baseline

From August 2024 onwards, freight rates eased from their July 2024 peak but stabilized at levels substantially above pre-crisis benchmarks:

- Asia–Europe rates: Settled at approximately $3,300–3,500/FEU by late 2024, representing 100–130% above pre-crisis levels (compared to pre-December 2023 rates of $1,500–1,700/FEU)

- Rate persistence: Contrary to expectations that rates would collapse once initial disruption was managed, they remained elevated throughout the extended disruption period, as supply-demand imbalances persisted

- Capacity management: Shipping lines employed capacity management strategies (blanking sailings, vessel repositioning) to maintain rate levels despite reduced demand in some markets

Phase 3 (October 2025–January 2026): Modest Rate Decline but Sustained Elevation

Following the Gaza ceasefire and tentative Red Sea recovery, freight rates declined modestly but remained well above pre-crisis baselines:

- Far East to North Europe: $2,100/FEU (as of late 2025), representing 39% above December 1, 2023 baselineof $1,506/FEU

- Far East to Mediterranean: $3,125/FEU, representing 68% above baseline of $1,857/FEU

- Transpacific rates: Approximately $2,274/FEU, compared to pre-crisis baseline of $1,643/FEU—a 38% premium

Importantly, even after 15 months of reduced threat levels and the Gaza ceasefire, rates remained significantly elevated, illustrating the persistence of geopolitical risk premiums in maritime commerce.

Operational Cost Analysis: The Per-Voyage Impact

Beyond freight rates (pricing for shipping services), the Red Sea crisis directly increased operational costs for vessel operators through fuel consumption, crew expenses, and opportunity costs:

Fuel Costs:

The extended voyage via the Cape of Good Hope requires substantially additional fuel:

- Distance increase: Cape route adds 3,500–4,000 nautical miles compared to Suez routing

- Fuel consumption increase: Large container vessels (15,000+ TEU) require approximately 800–1,300 tons additional fuel per voyage on the Cape route

- Fuel cost impact: At VLSFO (very low sulfur fuel oil) prices of $650/ton (2025 levels), this translates to $500,000–$900,000 additional fuel cost per voyage

- Total per-voyage additional fuel cost: Approximately $1–1.5 million depending on vessel size and fuel prices

Direct Additional Costs Per Voyage (Cape Route vs. Suez):

| Cost Component | Annual Impact (Large Container Vessel) |

|---|---|

| Fuel cost increase | $200,000–400,000 per voyage or $3–5 million annually |

| Crew wages (extended voyage) | $50,000–100,000 per voyage or $1–2 million annually |

| Insurance premium differential | Varies; Red Sea route higher during crisis ($300K–500K premium) but Cape route lower in normal markets |

| Suez Canal fees avoided | -$500,000–700,000 (offset against Cape costs) |

| Total net annual cost increase | $1–3 million per vessel depending on voyage frequency and rate structure |

Opportunity Costs and Fleet Efficiency:

The extended 10–14 day transit time for Cape routing reduces annual vessel productivity:

- Voyage reduction: 20% fewer annual Asia–Europe round-trip voyages (14–15 voyages/year vs. 17–18 voyages/year on Suez route)

- Revenue impact: For a 15,000 TEU vessel earning $50,000–70,000/day in charter rates, this represents $3–5 million in forgone annual revenue per vessel

- Fleet-wide impact: With approximately 10,000+ container vessels on Asia–Europe routes, the opportunity cost to the global shipping industry is estimated at $20–40 billion annually during disruption periods

Global Economic Impact and Inflation Transmission

The freight rate and operational cost impacts translated directly into global inflationary pressures:

Transmission Mechanisms:

- Import Price Inflation: According to IMF analysis, a doubling of maritime transport costs results in a 0.7 percentage point increase in global consumer price index and 0.3–0.5 percentage point increase in headline inflation

- Supply Chain Cost Pass-Through: Freight rate increases are rapidly transmitted to retail prices for imported goods. Studies indicate that 70–85% of freight cost increases pass through to consumer prices within 6–12 months, particularly for non-commodity goods (electronics, apparel, furniture)

- Developing Country Vulnerability: Small island developing states (SIDS) and least developed countries (LDCs) face disproportionate inflation impacts, as transport costs may constitute 8–12% of total import value(compared to 2–3% for developed economies). For countries like Mauritius, Fiji, and Bangladesh, the Red Sea disruption directly contributed to inflation rates 3–5 percentage points above developed country benchmarks in 2024

Quantified Global Impacts (2024–2025):

- Global supply chain cost increase: Estimated at $15–20 billion annually while Red Sea disruption persists

- Food price inflation contribution: The disruption contributed approximately 0.3–0.5 percentage points to global food price inflation in 2024, particularly affecting grain prices (wheat, rice) flowing through the corridor

- Manufacturing cost inflation: Semiconductor and electronics supply chains experienced 10–15% cost increases attributable partly to elevated freight rates and extended supply chain times

- Developing country inflation: LDCs experienced 0.5–1.5 percentage point higher inflation attributable to Red Sea disruption, with particular impact on food and energy-importing nations

Quantitative Synthesis: The Scope of Disruption

The Red Sea crisis, quantified comprehensively, represents:

- 52.5% reduction in Red Sea/Suez Canal traffic (from baseline to lowest point in early 2024)

- Sustained 60% suppression of traffic as of January 2026 despite ceasefire announcements

- Freight rate increases of 100–350% on primary Asia–Europe and Asia–Mediterranean routes during peak disruption

- $1–3 million per vessel additional operational costs on Cape routing

- $15–20 billion annual global supply chain cost increase

- 0.3–0.5 percentage point contribution to global inflation in 2024–2025

- Disproportionate impact on developing countries, with LDCs and SIDS experiencing 0.5–1.5 percentage point additional inflation

These quantitative impacts demonstrate that the Red Sea crisis, while originating in regional geopolitical tensions between Iran, Israel, and Yemen’s internal conflict, has become a major driver of global economic disruption, supply chain fragmentation, and inflationary pressures affecting all economies.

2: Restructuring Global Shipping Networks

2.1 The Cape of Good Hope Detour: From Emergency Response to Structural Baseline

The immediate shipping industry response to Houthi attacks in late 2023 was dramatic and decisive: diversion away from the Red Sea and Suez Canal. What began as an emergency rerouting decision evolved within months into a structural reorganization of global shipping networks. By January 2026, the Cape of Good Hope route has become embedded into carrier operating strategies, functionally equivalent to pre-crisis baselines regardless of formal threat assessments.

Volume Surge and Persistent Elevation

Cape traffic surged 191% above 2023 levels by 2024, with approximately 80% of container liners operating on Cape-based routing by mid-2024. In contrast, Suez Canal traffic collapsed 57.5% from baseline 4.0 million metric tons per day to 1.7 million metric tons. This volume shift was accompanied by a broader supply chain lengthening: global ton-miles increased a record 6% in 2024, representing nearly three times faster growth than actual trade volume (2.2%)—indicating structural supply chain extension rather than demand growth.

As of January 2026, despite the Gaza ceasefire (October 2025) and reduced Houthi attack frequency, Red Sea traffic remains approximately 60% below pre-crisis levels, with most Asia-Europe services continuing via Cape routing. This persistence of rerouting despite reduced threat frequency indicates that shipping companies have reorganized their infrastructure around the extended route, making rapid reversions economically suboptimal.

Distance and Time Dimensions

The Cape of Good Hope routing fundamentally extends global supply chains:

- Shanghai to Rotterdam: Suez route requires 11,000 nautical miles and 28 days; Cape route requires 15,000+ nautical miles and 40 days

- Distance penalty: 4,000+ additional nautical miles extending voyages by approximately 40%

This extension reduces vessel carrying capacity on an annual basis:

- Annual voyage capacity declines approximately 20% per vessel on Cape routing compared to Suez

- A 20,000 TEU vessel conducting 15 Suez voyages annually (28-day cycle) yields only 12 Cape voyages annually (40-day cycle)

- At typical charter rates of $50,000–$70,000/day, this represents $3–5 million in forgone annual revenue per vessel

Operational Cost Structure: Fuel, Insurance, and Crew

The Cape route imposes substantial cost burdens that sustain rerouting even as threat levels decline:

Fuel Costs:

- Additional consumption: 800–1,300 metric tons per voyage

- At 2025 VLSFO pricing (~$650/ton): $500,000–$850,000 additional cost per voyage

- Annual impact per large vessel: $6–10.2 million (based on 12 annual voyages)

- Fleet-wide aggregate (3,000–4,000 container vessels): $18–40 billion annually during sustained rerouting

Crew and Operational Expenses:

- Extended voyage duration adds $50,000–$100,000 in crew costs per voyage

- Annual impact per vessel: $600,000–$1.2 million

- Suez Canal transit fees avoided (partial offset): $300,000–$700,000 per passage

Net Cost Premium:

Aggregate operational costs per Cape voyage exceed Suez routing by $1–3 million per vessel, depending on fuel prices and charter rates.

Container Losses and Safety Hazards

The concentrated shift to Cape routing has increased maritime casualties. The Cape region experiences hazardous conditions—the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties latitudes create sustained rough seas and extreme weather that pose risks even to modern vessels.

2024 container loss data:

- 576 containers lost overboard globally in 2024, more than double the 221 lost in 2023

- 35% of global container losses in 2024 occurred at the Cape of Good Hope, approximately 200 containers

- Three major incidents at the Cape involved losses of 44, 46, and 99 containers respectively

- The surge was “driven in large part by disruptions to trade through the Red Sea, where persistent attacks prompted global carriers to divert traffic to the Cape of Good Hope”

This concentration reflects both the volume surge and the hazardous environmental conditions. While absolute losses remain below historical averages, the regional concentration and year-over-year doubling signal that Cape routing carries operational safety risks factored into carrier decision-making.

2.2 Dual-Route Equilibria: Risk, Insurance, and Carrier Strategies

Despite apparent Cape dominance, the global shipping network has not bifurcated into a single route. A dual-route equilibrium has emerged: the Suez Canal receives selective traffic while the Cape route dominates volume, creating a conditional pricing structure fundamentally different from pre-crisis patterns. Carriers employ mixed routing strategies reflecting risk-adjusted economics and unresolved geopolitical conditions.

War Risk Insurance as the Structural Cost Driver

The most consequential structural change is maritime war risk insurance repricing. War risk premiums—charged as a percentage of hull and machinery value per voyage—have become the effective mechanism making the Cape route economically competitive with the Suez route despite its operational inefficiency.

War Risk Premium Evolution:

| Region/Route | Pre-2023 | Peak 2024 | Current 2025 | % Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red Sea transit | 0.10% | 1.0% | 0.75% | +650% |

| Gulf of Aden | 0.05% | 1.0% | 0.40% | +700% |

| Suez approach | 0.02% | 0.50% | 0.15% | +650% |

| Persian Gulf | 0.20% | 0.50% | 0.50% | +150% |

| Cape of Good Hope | 0.05% | 0.15% | 0.10% | +100% |

Sources: UK P&I Club data, Freightamigo 2025, Lloyd’s Market Association

The critical finding: Red Sea war risk premiums remain at 0.75% even after the October 2025 ceasefire, representing 5 times higher than pre-2023 baseline levels. This sustained elevation persists despite reduced threat frequency, indicating that insurance markets price the risk as structural rather than temporary.

Per-Voyage Financial Translation:

For a 20,000 TEU container vessel (hull/machinery value ~$165M):

- Red Sea Suez-route premium: 0.75% × $165M = $1.24M per voyage

- Cape-route premium: 0.10% × $165M = $165K per voyage

- Insurance differential: $1.075 million per voyage favoring the Cape route

This insurance cost advantage alone makes Cape routing economically competitive despite additional fuel and crew expenses. The insurance repricing has transformed Cape routing from a temporary disruption response into a structurally sustainable alternative.

Carrier Routing Strategies: Selective Suez Operations and Mixed Portfolios

Major shipping lines (Maersk, MSC, CMA CGM, Hapag-Lloyd) have not adopted uniform strategies. Instead, they employ mixed portfolio approaches:

- Cape-routed services form the primary Asia-Europe backbone (70–80% of scheduled sailings)

- Selective trial transits through Suez occur during perceived geopolitical calm periods

- Both routes are maintained to allow customer choice and risk allocation

- Voyage-by-voyage decisions adjust routing based on real-time threat assessments

This mixed strategy reflects rational risk management: maintaining Suez services preserves optionality if geopolitical conditions stabilize and war risk premiums normalize, while concentrated Cape routing insulates carriers from escalation risks. Offering both routes allows carriers to segment demand—risk-averse shippers pay premiums for faster Suez transit; price-sensitive shippers accept longer Cape voyage durations.

Evidence of Mixed Routing:

Suez Canal monthly transits reached 229 vessels in October 2025 following the Gaza ceasefire but recovered only to 50–60% of 2023 baseline traffic. This represents recovery overlay rather than route reversal: carriers are adding selective Suez services atop stabilized Cape operations rather than abandoning the extended route.

Risk Perception vs. Risk Reality: Why Rerouting Persists

Despite attack frequency declining from daily (January–February 2024) to sporadic (March–September 2025) to announced pause (October 2025–present), carrier risk perception has not normalized. This divergence reflects three structural factors:

1. Geopolitical Driver Persistence: The Gaza conflict and Israel–Palestine tensions remain unresolved, with no clear pathway to fundamental de-escalation. Carriers rationally assess the current operational pause as potentially temporary rather than permanent, maintaining precautionary routing strategies.

2. Houthi Capability Demonstration: Over 190 documented maritime attacks have established that the movement possesses sustained military capability independent of Iran’s immediate strategic direction. This demonstrated capacity enables rapid renewed escalation from operational pause states.

3. Insurance Market Ratchet Effect: War risk insurance remains repriced at elevated levels even during low-threat periods. Carriers must internalize elevated premiums regardless of attack frequency, and insurance markets normalize rates only when threats are perceived as eliminated, not merely suspended.

The combined effect shifts routing from threat-responsive (attack frequency-driven) to strategy-responsive (geopolitical incentive-driven). Carriers plan Cape-dominant networks because underlying geopolitical incentives for Houthi action—Palestinian solidarity, opposition to regional hegemony, Iranian strategic interests—remain structurally unresolved.

2.3 Port and Corridor Winners and Losers in Africa, Europe, and Asia

The Cape-dependent restructuring has produced highly asymmetric impacts on port development and regional competitive positioning. Some corridors experience unprecedented growth while others face structural disadvantage.

Winners: West African Ports and Transhipment Network Emergence

West African ports (Tema, Abidjan, Lomé, Kribi) have benefited from a unique geographic advantage: vessels rerouting around Africa necessarily traverse West African waters and can access these ports with minimal distance penalty compared to alternative Mediterranean transhipment routing.

Quantified Growth:

- West African container trade: ~50% expansion in less than a decade

- First-half 2025: Volumes surged 30% compared to same period 2024

- Broader Africa: Container traffic grew 57% in recent years, second only to Asia’s 64% growth

- ULCV capability deployment: MSC’s April 2025 deployment of 24,000 TEU mega-ships to West African ports (MSC Diletta inaugurating service April 23, 2025) marked structural capacity threshold achievement

Infrastructure Modernization:

Historically seen as secondary markets, West African ports have upgraded rapidly:

- Maersk terminals in Abidjan and Tema validated for 20,000+ TEU vessel handling

- MSC redesigned the Africa Express Service (April 2025) to accommodate 24,000 TEU vessels, enabling direct transhipment from Asia without Mediterranean intermediate stops

- Ports upgraded terminal infrastructure including ship-to-shore cranes, yard expansion, and reefer connectivity

Transhipment Network Restructuring:

The innovation is that West African ports now function as viable transhipment hubs for Asia–West Africa and Asia–Europe business, eliminating dependency on distant Mediterranean centers. Vessels on Cape-routed services no longer require Mediterranean transhipment before serving West African markets, reducing inventory carrying costs and supply chain complexity.

Competitive Impact on Mediterranean Hubs:

West Mediterranean calls to West Africa declined from 69 calls (Q3 2023) to 41 calls (Q3 2025), a 40% reduction, representing 34.6% capacity loss in allocated transhipment services.

Winners: East African Ports and Indian Ocean Corridors

East Africa:

Ports of Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) and Mombasa (Kenya) attract substantial investment as Cape routing gateway infrastructure:

- Tanzania: Container traffic growing 12.5% CAGR, reaching 236,458 TEU

- Kenya: Exports 188,748 TEU with 6.8% CAGR

- Intra-African trade: 12.4% year-over-year growth, partly driven by improved regional port connectivity

- Infrastructure expansion: Major capacity-doubling projects underway, with combined East African growth forecast of +15–20% in 2026, potentially reaching 1.5–1.7 million TEU combined throughput

Salalah, Oman:

Port of Salalah presents mixed performance—container volumes declined but general cargo surged:

- Q1 2025: Container throughput 823,000 TEU, down 6% from 878,000 TEU (Q1 2024)

- General cargo surge: Terminal handled 6.4M tons (2025) vs 5.8M tons (2024), a 11% increase

- 9-month performance (ending Sept 2025): 3.2M TEU, up 26% from 2.5M TEU prior year, indicating recovery momentum

- Infrastructure completion: $300 million expansion with 10 next-generation ship-to-shore cranes and 2,000 reefer plugs

Indian Ports:

India’s positioned on the Cape-routed Asia–Europe corridor:

- Container traffic: Increased from 8.20M TEU (FY16) to 12.28M TEU (FY24), a 7.7% CAGR

- Major port expansions: JNPT, Mundra, Chennai, and Visakhapatnam implementing 20–30% capacity increases over two years, with long-term capacity target exceeding 50 million TEU within five years

- Trade lane growth: India-Southeast Asia traffic accelerating as “China+1” manufacturing diversification intensifies

Winners: Alternative Mediterranean and Atlantic Gateway Ports

Mediterranean ports have adapted by positioning as secondary gateways rather than primary transhipment hubs:

- Port of Valencia (Spain): 3.4% growth in container traffic (2025), with exports up 5.56% and imports up 15.55%

- Genoa (Italy): Handling increased diverted Asia-Europe trade flows